That's the question on everyone's lips as we at the Morton School prepare for our Quality Review, which is right around the corner. Don't say it like, "What'cha doin'?", making it sound like a casual inquiry into what is going on in one's classroom or life. No, you have to fully pronounce all four words--"What are you doing," emphasis on "doing," and then follow it up with something like "to raise achievement for your Hispanic students" or "to improve reading scores among your lowest one-third citywide"?

That's the question on everyone's lips as we at the Morton School prepare for our Quality Review, which is right around the corner. Don't say it like, "What'cha doin'?", making it sound like a casual inquiry into what is going on in one's classroom or life. No, you have to fully pronounce all four words--"What are you doing," emphasis on "doing," and then follow it up with something like "to raise achievement for your Hispanic students" or "to improve reading scores among your lowest one-third citywide"?Gosh, I was planning on picking my nose until a week or two before the ELA exam, I guess. What kind of a question is that?

The other day I was discussing with a colleague a couple of her former students that are giving me a hard time--not behaviorally, but academically. I spend much more one-on-one time with these students because they are struggling. All of them have been identified for extra help. But they don't do the things I ask them to do in conferences. One of them in particular pays little to no attention in class. Another does almost no homework. They're good kids, but not especially good students, and I've really hit a wall with them.

"Well, at some point," my colleague said, "free will comes into play, and they are exercising it."

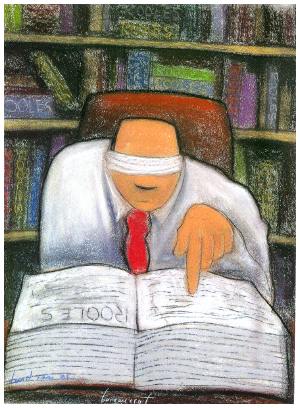

So I really hate that question, "What are you DOING?" What am I doing? Well, I'm trying to share important contemporary texts and great works of literature with all my children, even my "lowest third citywide" or my "ELL population." The more I teach and the more I watch children, I'm convinced that E.D. Hirsch and Dan Willingham are right, that discrete "reading skills" can't be taught and that children need a wide variety of texts, cultural experiences, and background knowledge to create meaning out of any text. I'm allowing my students the greatest degree of choice I possibly can with most assignments, while still trying to make sure they all have a baseline of content knowledge and writing competency to enable them to survive in any level of high school class. I'm spending my own free time and money gathering books for my classroom library. I'm spending nights and weekends reading professional books, grading papers, blogging, watching films, and collecting tidbits that might be useful someday in my classroom. That's what I'm DOING.

Not to stroke my own ego too much, but I try to make class exciting and worthwhile for my kids--that's what I'm DOING--and if they decide not to take advantage of that, I'm not sure I can DO much else. My students are teenagers and my struggling ones didn't suddenly start drowning when they entered my class. Perhaps the question to start asking is, "What are they doing?"

Homework? No.

Paying attention in class? No.

Writing? No.

Reading? No. And there's no excuse at all for that last one; I have a wonderful classroom library (built at least partially with my own free time and money) with a wide variety of nice, recent books that most kids love poring over.

I'm not saying that I'm giving up on these kids. But I hate being treated like I already have, like clearly there's something I'm not doing, or else they would be succeeding. I'm still looking for ways to help them, but I can't imagine that they wouldn't already doing better if they were lifting a finger in their own interests.